The Real Reason Groceries Are Expensive

The other night I ran into my neighbor, Michelle. She was loaded down with kids and bags of food. Exasperated, Michelle said, “I never thought three kids could eat this much, or that feeding our family would be so expensive.”

There is no doubt, it is painful going to the grocery store. Everything costs more, and the average family has few options. Although you can cut back on a movie or trip, it’s really hard to cut back on food for more than a few days.

Michelle asked if I thought grocery stores were “gouging” customers. She was also curious as to how we got here.

As is no surprise, there is much political grandstanding during election season. However, politicians might want to take an Economics 101 course.

If grocery stores were truly taking advantage of customers, then why do they only earn net profit margins of 1.5% to 2% per year? If they are gouging, they aren’t doing a very good job of it. The grocery business remains one of the most competitive and lowest profit businesses. According to the National Grocers Association, the average grocery store netted a profit of about 2.5% a decade ago. Over the last decade they have fallen 20% to 40%.

Michelle looked at me quizzically and asked, “Then why are things so expensive?”

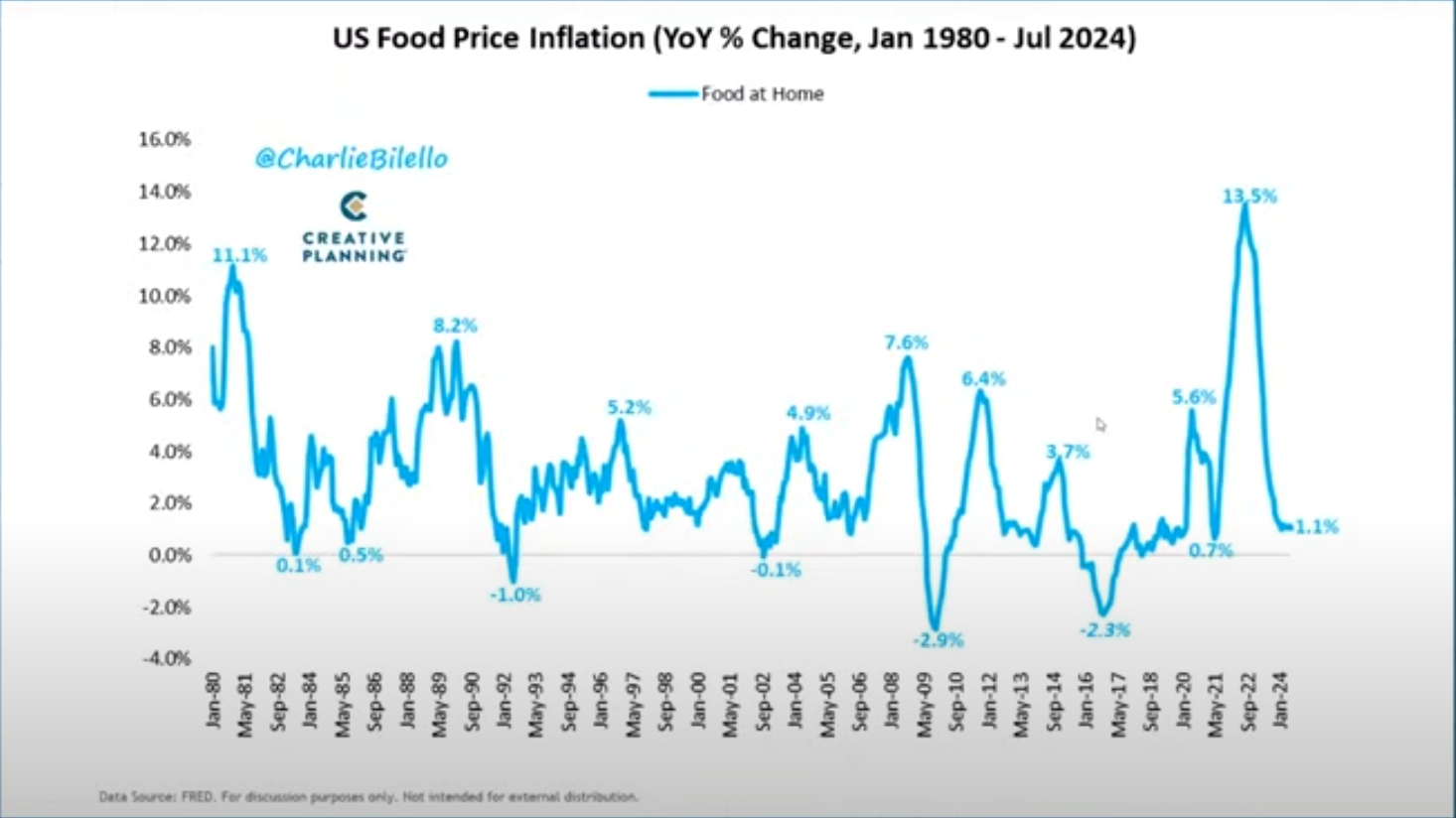

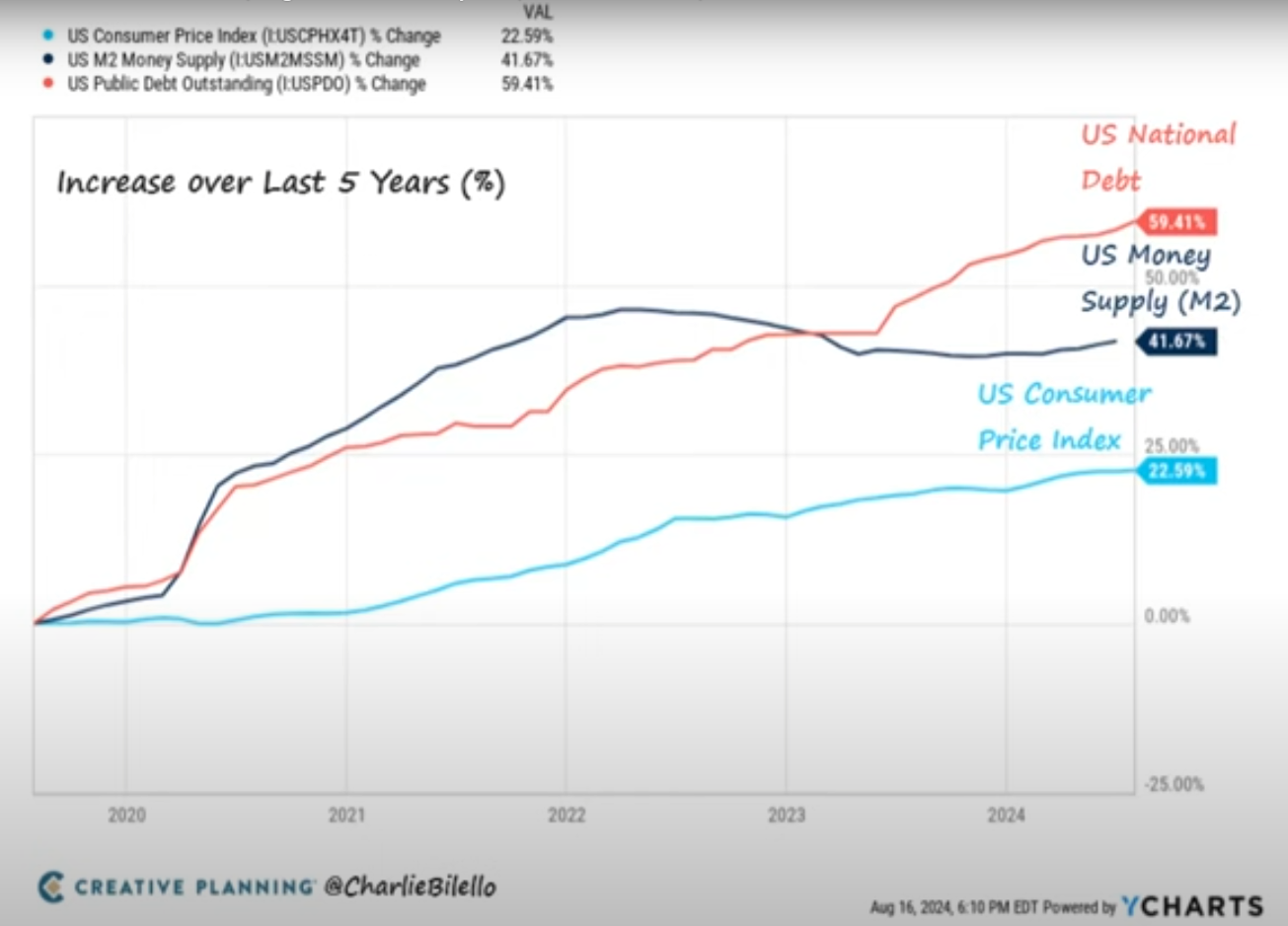

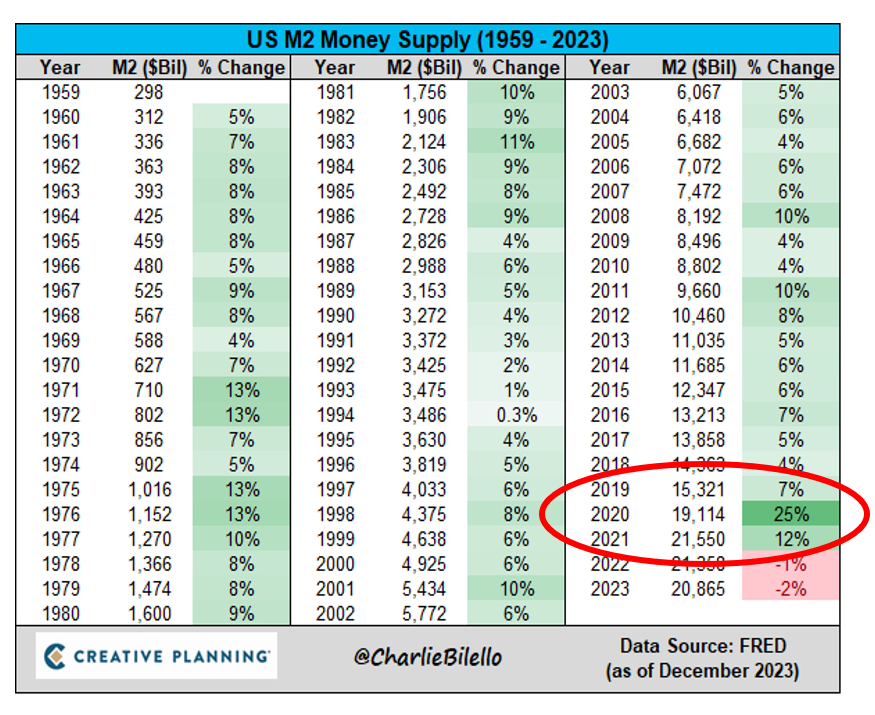

Simply put, the money supply increased by 40% from 2019 to 2021. Going into the pandemic, there was approximately $15 trillion in money circulating. This is called M2 Money Supply.

When the pandemic struck, the economy was free-falling, and the stock market fell 34% in one month.

Our elected leaders devised stimulus plans, free money for virtually every American. The goal was to increase sales and stimulate a stumbling economy. Handing out free money increased our money supply from $15 trillion to $21.5 trillion. Both Trump and Biden Administrations contributed to the free money programs. To make this happen, the national debt increased 60%.

Conversely, if a stimulus plan had not been implemented, we were headed for deflation. Deflation (prices falling) is far worse as everyone pulls back on spending and the economy spirals downward. This happened during the Great Depression.

The problem with “free” money is there is still a limited supply of goods and services. Basic economics dictates that when demand is stimulated by tons of cash, equilibrium prices on limited stuff increases. As such, people spent money and the economy grew. As the economy grew, prices went up.

This stimulus program was the equivalent of everyone winning the lottery at once. They were flush with cash and ready to party.

Increasing prices, in isolation, is not a problem if people spend “free” stimulus money. However, most of the free money has been spent leaving the average American tapped out while nursing a financial hangover. At the same time, the price of housing, cars, trips and wages all increased. Now consumers must deal with permanently elevated equilibrium prices.

Michelle looked at me and said, “I think I understand. However, won’t price controls fix things?”

This is an even scarier idea.

Price controls happen when governments impose restrictions on prices of goods and services. Versions of this can be seen in weak economies such as communist or socialist nations. Theoretically, price controls are implemented to prevent excessive inflation which should make things more affordable.

However, we don’t live in a closed economy. We don’t have the ability to simply say, “From now on, sugar is $1 per pound.” We live in a dynamic global economy in which supply and pricing is always adjusting.

If price controls are set below the market equilibrium, then greater demand leads to less supply. As we saw in the 1970’s with gasoline, we incur shortages and waiting lists.

Price controls also lead to reduced quality as producers attempt to cut costs to maintain profitability. If profit margins fall, price controls reduce innovation and development. This also stifles employment.

Shortages from price controls also lead to the emergence of black markets. This leads to corruption, exploitation and reductions in tax revenue. In the process, the people who are most vulnerable are not helped by price controls but are hurt even further.

Although Michelle wished for a silver bullet, she recognized it was unlikely. In her very pragmatic way, she said, “I guess we will have to work a little harder and save a little more.”

Dave Sather is a Certified Financial Planner and the CEO of the Sather Financial Group, a fee-only strategic planning and investment management firm.